,--.-----.--.

|--|-----|--|

|--| |--|

| |-----| |

__|--| |--|__

/ | |-----| | \ mm mmmm mmm

/ \__|-----|__/ \ ## m" "m m" "

/ ______---______ \/\ # # # # #

/ / \ \/ #mm# # # #

{ / _ _ _ \ } # # #mm# "mmm"

| { / | | . | | /| } |-,

| | \ |_| . |_| _|_ | | | mmmm mmmm mmmm mmmm

| { } |-' " "# m" "m " "# m" "m

{ \ / } m" # m # m" # m #

\ `------___------' /\ m" # # m" # #

\ __|-----|__ /\/ m#mmmm #mm# m#mmmm #mm#

\ / |-----| \ /

\ |--| |--| /

--| |-----| |--

|--| |--|

|--|-----|--|

`--'-----`--'

Advent of Code is a popular yearly programming competition. It's an Advent calendar of small programming puzzles for a variety of skill sets and levels that can be solved in any programming language you like.

Puzzles are released daily throughout December. More than 150k people take part in this event. The toughest battle to solve each puzzle as soon as possible to become the best on the global leaderboard.

In my timezone, puzzles are released at 6 o'clock in the morning. Since I'm a night owl, the biggest challenge for me here is to get up so early. I, therefore, set a different goal instead.

Subsecond

I want to develop a standalone, short, compact, fast and, elegant solution for each problem this year. In past competitions, I took part using the Rust language. I've been using it a lot for other projects lately, and believe it is a fantastic language to build performant, secure, and robust software. This has always sparked my interest so Rust is a good fit.

Last year I came across this article, solving all puzzles in under a second. Yes, in less than one second total. This inspired me to challenge myself to the same this year:

Solving Advent of Code 2020 in under a second on a single CPU core.

Spoiler alert: I succeeded!

What's in this for you?

In this article, I'd like to show you some optimizations I found appealing which I used to keep the solutions blazingly fast. I'll only talk about the most significant optimizations and the interesting bits. Most are algorithmic and are consequently language agnostic.

I'm just using basic time measurements on my machine. I won't be theoretically proving the efficiency of an approach. I optimized the runtime of my solutions based on my personal input. I did not make assumptions other than what is clear from the puzzle description though, so each solution should work for all inputs with comparable runtime. All user input is similar after all.

I hope this article will present you with some out-of-the-box approaches you can take away to make your future code more performant. Hence this piece is intended for programmers that value performance.

)

CHOO CHOO ' ))'

{// '"

"'' )

___ ___ ____ ____ ____ __||_

____ -- __ {___{{___{{___{(___(o)

---- ---- 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0'U'

code zooming past

Source code

Source code and measurements? See my solutions on GitHub:

https://github.com/timvisee/advent-of-code-2020

If you'd like to give these puzzles a try and haven't done so yet, I highly recommend doing so before you continue reading. It contains spoilers.

Now, let's get started with the interesting stuff.

Day 1: Report Repair

On the first day part 2, we're given a list of numbers. We must find 3 numbers that have a sum of 2020. All numbers are around 1000, so we're likely trying to find a pair of 3 small numbers.

I sort the list of numbers from small to large before trying to

find the correct pair, which decreases the runtime from 1.38ms to 7μs.

Yup, starting simple.

Day 6: Custom Customs

On day 6 part 1 we're trying to find the number of unique questions. There are 26 in total, represented as letters. I take a 32-bit integer and set the corresponding bit for each answer. I then count the number of ones. No expensive data structures are required.

cady: 00000010110000000000000000000010

ipldcyf: 00000000110100100100010000000010

xybgcd: 00000000110010000000000000000110

gcdy: 00000000110010000000000000000010

dygbc: 00000001110010000000000000000010

=OR=============================

00000011110110100100010000000110 -> 11

Part 2 is simple now: I take the same approach but use the AND operation instead of OR when setting bits.

Day 9: Encoding Error

On day 9 part 2 we must find a sequence of numbers in a list of numbers that sums up to a specific value.

The common approach seems to be to use a for in a for loop. This walks

over each position with the outer loop and tries to find a sequence with the

correct sum with the inner loop.

I'm using a dynamic sliding window approach instead (I better give it a fancy name you know). I start by sliding the head forward, making the window and the sum larger. When the sum becomes larger than the target value I stop. Then I start sliding the tail forward, making the window and the sequence sum smaller. When the sum becomes smaller than the target value I stop.

>> tail >> >> head >>

| |

+-----------+

... 35 20|15 25 47 40|62 55 65 95 102 ...

+-----------+

| tot: 127 |

I keep alternating between sliding the head and tail. Once the sum equals the target value, we've found the sequence and can solve the puzzle. This minimizes the number of required loops, making it more efficient.

Day 10: Adapter Array

On day 10 part 2 we get a list of adapter voltages. Adapters may be plugged into each other if the adapter is 1 to 3 volts higher than the adapter you're plugging into. The puzzle is to figure out how many distinct adapter arrangements are possible.

I started with a sorted list because you can only plug higher-rated adapters into lower-rated ones. The maximum difference is 3, so I soon discovered that you can chunk the sequence of adapters. Each chunk of adapters has a difference of 3, which only gives one way to connect between them. You can now process each chunk separately to find distinct arrangements, multiplying their calculations.

Chunks with adapters:

C1 >> C2 >> C3 >> C4 >> C5

-- -- -- -- --

1 4 10 15 19

5 11 16

6 12

7

-- -- -- -- --

1x 7x 4x 2x 1x

Ways to connect:

1 + 7 + 4 + 2 + 1 = 15

This resulted in chunks that always consisted of 2, 3, or 4 adapters. This makes it easy to find distinctions between them. I finally figured that I could optimize it to a fixed number of distinctions per chunk size greatly reducing complexity.

I found 74049191673856 distinct ways to connect all adapters in just 5μs. I

can't even count to 1 within that time.

Day 11: Seating System

On day 11 part 1 we're given a variation of Conway's Game of Life represented as a 2D arrangement of seats on a plane. Each iteration seat occupation changes based on a set of rules considering their neighbors, but seats don't move.

L.LL.LL.LL L = empty seat

LLLLLLL.LL . = nothing

L.L.L..L..

LLLL.LL.LL

L.LL.LL.LL

L.LLLLL.LL

..L.L.....

LLLLLLLLLL

L.LLLLLL.L

L.LLLLL.LL

With regular Game of Life you'd have to loop through all positions each iteration and evaluate all rules to determine their new state. Because this puzzle does not have a seat at every position (nor do seats always have 4 neighbors) our plane is more like a sparse array. A lot of cycles would be wasted if we'd keep looping over all plane positions.

I decided to make a list of all seat positions and their respective neighbors. This way I only had to go through this list of seats for each iteration. Determining what neighbors a seat has just needs to be performed once.

This is especially great for part 2 which makes things worse. It doesn't just consider direct neighbors anymore, but neighbors in line of sight making searching much more expensive. Luckily it doesn't affect my approach from the first part too much, as I only search once. This is much more efficient than looping through all positions and finding neighbors every time.

Day 12: Rain Risk

On day 12 part 1 we're given a sequence of navigation instructions for a ship. It includes cardinal directions, rotation, and forward instructions. We must figure out the distance between the start and destination position.

What makes this tricky is the rotation and forward instructions. The forward movement is dependent on your current rotation.

I use a single byte of which the first 4 bits define the current rotation. The

first bit means north, the second bit means east, et cetera. Because the ship

starts looking east, I start with the 0b01000100 pattern. For each rotation

instruction, I simply rotate the bits left or right. Rotating

right would update the direction to 0b00100010.

Direction bits, shift to rotate 90 degrees left or right:

<< rotate left << >> rotate right >>

... <> 01000100 <> 00100010 <> 00010001 <> 10001000 <> ...

Bit meaning:

[ y-1 ] [ y+1 ]

[north] [south]

| |

Direction bits 00100010 would move ship south (y+1)

| |

[east] [west]

[ x+1] [x-1 ]

To move forward I take this direction byte and use bitwise

arithmetic to update the ship position. This removes branching (if statements

and such) you'd normally expect for logic like this. Quite elegant.

Day 13: Shuttle Search

On day 13 part 2 you're given a series of bus lines, each having a fixed schedule. You must find the time where each bus leaves one after the other, in order.

time bus 7 bus 13 X X bus 59 X bus 31 bus 19

... . . . . . . . .

1068780 . . . . . . . .

1068781 D . . . . . . .

1068782 . D . . . . . .

1068783 . . D . . . . .

1068784 . . . D . . . .

1068785 . . . . D . . .

1068786 . . . . . D . .

1068787 . . . . . . D .

1068788 D . . . . . . D

1068789 . . . . . . . .

...

My initial thought was just to brute force through all times. The correct answer turns out to be very large (more than 640 trillion), making this impossible within a short time. I was unable to optimize this myself with basic mathematics due to the weird constraints.

Searching for the problem semantics and related keywords online revealed the Chinese Remainder

Theorem. It is very similar to the given problem and shows an efficient

way to solve it with sample code. With minimal changes, I solved this seemingly

impossible puzzle and the solution finds the answer in just 4μs.

The important lesson here is that many Advent of Code problems resemble some well-defined algorithm or at least part of it. If you can't solve it yourself, try to find a suitable algorithm. Finding such an algorithm makes solving the problem child's play. This is super interesting for learning about new algorithms and approaches as well.

Day 15: Rambunctious Recitation

Day 15 requires you to continue a number sequence to find the number at a given position. The puzzle description explains the rules quite well. The second part gets tricky: it asks you the 30 millionth position. The problem is that for each number you have to traverse all previous numbers based on the given rules. This becomes super expensive for higher positions. For 30 million numbers this means traversing 450 trillion (!) numbers.

Given: 6, 4, 12, 1, 20, 0, 16

2back 2back 1back new new 6back 3back

| | | | | | |

6, 4, 12, 1, 20, 0, 16, 0, 2, 0, 2, 2, 1, 9, 0, 5, 0, 2, 6, 0, 3, ...

| | | | | | | |

new new 2back 9back 5back 2back new new

The sequence appears to be the Van Eck sequence (see this fantastic Numberpfile video on it). To my surprise, there doesn't seem to be an efficient algorithm for generating the sequence. The sequence does not repeat, nor does it have a known pattern that would help with generating. Many people (a lot smarter than I am) have taken up the challenge to find a more efficient method, but without result. This means I don't have to give it a try. Instead, I have to be careful to use the correct logic and data structures to keep my sequence generator as fast as possible.

I opted to use a lookup table approach with an array and hash map combination. Because the last position of a number is important, the table is used for this with the number as a key and the last position as a value. This way generating the next number only requires a single lookup instead of traversing all previous numbers.

Instead of just using a fixed array or hash map for the lookup table as a whole, I split it in a low and high side at the 3 million mark. The low side is a fixed array, the high side utilizes a hash map. This turns out to be much faster than using just either of the two, improving runtime by 30%. This is super interesting to me, and I didn't expect it to be so much faster. It likely has to do with more efficient CPU cache usage on my system, where the low side with the array is dense, and the high side with the hash map is sparse, though I haven't looked into the details. This shows that using a single data structure isn't always the best approach, even though that might be against your expectations.

Sequence example:

6, 4, 12, 1, 20, 0, 16, 0, 2, 0, 2, 2, 1, 9, 0, 5, 0, 2, 6, 0, 3, ...

Last position lookup tables:

LOW SIDE ARRAY 0..3M HIGH SIDE MAP 3M..30M

+-------+----------+ +------+------------+

| index | last pos | | num | last pos |

+-------+----------+ +------+------------+

| 0 | 20 | | 3M | 3.2M |

| 1 | 13 | | 3.2M | 8.3M |

| 2 | 18 | | 3.5M | 9.1M |

| 3 | 21 | | 3.6M | 4.9M |

| 4 | 2 | | 3.7M | 11.2M |

| 5 | 16 | | .. | .. |

| .. | .. | | | |

| 3M | 0 | | | |

+-------+----------+ +------+------------+

My final solution completes in 511ms. Quite the achievement, as it seems

rather fast compared to others. This is the most costly puzzle

when looking at runtime. It alone takes up 73% of my total runtime and consumes

more than half of my 1-second target. Ouch...

Day 17: Conway Cubes

For day 17 Conway's Game of Life returns (who'd have thought looking at its title), though it has a special twist. You have to figure out how many 'cubes' are active after a number of cycles, but this time we're doing it in 3D space. The puzzle input is a 2D slice that serves as starting state.

The first optimization I implemented was to limit the search space each cycle. This space starts with the input size and grows by one in each direction for each iteration. This limits the number of cubes to check, as distant cubes can't be active yet. Easy.

Because the initial state is a 2D slice, I noticed another interesting property. As the 2D slice is effectively the same on the two sides of the third axis, it expands with the same pattern in both directions. This means that the third axis is mirrored from the center (the slice). I only have to simulate one of these two sides and multiply the cube count to get the answer we need. This halves the number of operations reducing runtime.

2D example with 1D (column) input which mirrors:

single input column

|

---------------

#---##---##---#

#--#--#-#--#--#

---#-#---#-#---

----#-----#----

--------------- what the field

-----#---#----- <-- looks like after

----##---##---- some cycles

---##-----##---

---------------

-----#####-----

------###------

------###------

|

<<< | >>>

|

mirrors left and right

Part 2 gets even better. The puzzle is similar but simulates in 4D space. To accommodate for this the rules have changed slightly, but the input is still the same 2D slice. This is fantastic because this means not just one but two axis are mirrored now. With the same optimization, I now need to simulate only ¼th of the space, making the solution 4 times quicker!

Day 20: Jurassic Jigsaw

Day 20 involves a jigsaw puzzle. Each piece is a 10×10 matrix of bits. All pieces form a larger square. The bits on the edges between two pieces must align. Every piece can be placed anywhere and may need to be rotated or flipped in any direction. That's a lot of combinations.

Placed tiles for small example puzzle:

T3: T9: T2:

..##. ...## #.##.

##..# #...# #.###

#...# #..#. .....

####. ....# #...#

##.## ##### ###.#

T1: T6: T5:

##.## ##### ###.#

.#.## #..## ###.#

..#.. ..#.. .###.

###.. .#.#. ..#.#

..##. ..### #...#

T7: T4: T8:

..##. ..### #...#

#..#. .#..# #..##

##.#. .#.#. .#.#.

.#### ####. .###.

..##. .#### #.###

To solve the first part you must figure out what pieces are placed in the 4 corners. @gkhill gave me the insight (thanks for that!) that corner pieces have two edges that don't connect to anything and likely won't match any other edge. Now I only had to find 4 pieces with edges that didn't match any other edge. In the example above the tiles, T3, T2, T7, and T8 all have 2 edges that don't match any other. Rather simple. That worked.

In part 2 I use tricks like just rotating/flipping tile edges instead of the full tile body while positioning them. I won't go into further detail because it doesn't seem to affect the total runtime too much. But you might find the implementation interesting.

Day 23: Crab Cups

Day 23 involves a game of moving cups. The cups are arranged in a circle. Each is labeled with a unique number. To solve the puzzle you have to move chunks of them around based on a set of rules for a specific number of turns, to get a final sequence.

Part 2 gives you one million cups, for which you've to do ten million moves. That's a lot! Representing the cups as a list of numbers in an array turns out to be very inefficiënt. For each iteration, you'd have to move a chunk of cups through the list. This requires shifting a lot of items in memory, resulting in many reallocations. That's slow, no good!

Instead, I choose to utilize a structure that essentially functions like a linked list. I allocated an array with one item for each cup. The array is indexed by cup number. For each cup, it holds the number of the next cup. It effectively points to the following cup in the arrangement, looping the sequence.

This is great because it makes moving a chunk of cups around super cheap. Instead of having to shift a lot of items through memory, you just have to update 3 pointers. To move a chunk of cups, I:

- update the cup before the old chunk position, to point to the cup after the old chunk position,

- update the cup before the new chunk position, to point to the first cup of the chunk,

- update the last cup of the chunk, to point to the cup after the new chunk position.

Cup sequence: 3 8 9 1 2 5 4 6 7

Linked list, storing our sequence:

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | <- cup label

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| 2 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 1 | <- points to (next cup)

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

To move chunk [8, 9, 1] after 5:

Cup sequence: 3 |8 9 1| 2 5 4 6 7

+-------+

v

+-------+

Cup sequence: 3 2 5 |8 9 1| 4 6 7

+---------- 1. change 3 to point to 2

| +-- 2. change 5 to point to 8

+-------|-------|-- 3. change 1 to point to 4

| | |

| | |

v v v

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | <- cup label

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 1 | <- points to (next cup)

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

As a bonus; you can instantly find a cup with a specified number by its index. And because the last cup can point to the first an edge case is removed for handling the sequence as a loop. Brilliant!

The final implementation runs 192ms, making it the second slowest solution.

The optimizations are useful here to keep everything under one second.

Day 24: Lobby Layout

Day 24 involves a floor of hexagonal tiles. You're given a list of directions to move on it, the target tile must be flipped between black and white.

A hexagonal grid can be tricky to comprehend. I just work with it as if it's a square (but askew) grid. Seeing a problem like this differently can greatly reduce its complexity.

_____ _____ _____

/ \ / \ / \

_____/ -2,-1 \_____/ 0,-1 \_____/ 2,-1 \_____

/ \ / \ / \ / \

/ -3,-1 \_____/ -1,-1 \_____/ 1,-1 \_____/ 3,-1 \

\ / \ / \ / \ /

\_____/ -2,0 \_____/ 0,0 \_____/ 2,0 \_____/

/ \ / \ / \ / \

/ -3,0 \_____/ -1,0 \_____/ 1,0 \_____/ 3,0 \

\ / \ / \ / \ /

\_____/ -2,1 \_____/ 0,1 \_____/ 2,1 \_____/

/ \ / \ / \ / \

/ -3,1 \_____/ -1,1 \_____/ 1,1 \_____/ 3,1 \

\ / \ / \ / \ /

\_____/ \_____/ \_____/ \_____/

Part 2 challenges us to a Game of Life one last time. This time we're using the hexagonal grid, however, ouch. The floor from part 1 is our starting state. A set of rules is provided to flip tiles between black and white based on their neighboring tiles.

I kept the square grid from part 1. Though each square tile has 6 neighbors (including 2 diagonal) instead of just 4 to match what a real hexagonal grid would be like. Based on the rules we only have to consider tiles that have at least one neighboring black tile. This makes processing the infinitely sized floor cheaper.

I compile a list of all neighbor tiles for each black tile and

count their occurrence number. After collecting this list I loop over all these

neighbors with their occurrence count to process the rules accordingly. Using

this method I skip looping over a huge amount of useless tiles and asserting the

rules becomes simple, similar to what I've done on day

13. Doing just 100 iterations as the puzzle specifies

takes 43.2ms, pretty expensive I think. With 656ms total runtime so far I'm

still well under my 1-second target though.

Day 25: Combo Breaker

On day 25 you're challenged to obtain the encryption key to break a card-based door locking system. A set of cryptography rules is given, along with the public key of the card and the door lock, and some additional parameters.

You have to brute force your way to the final encryption key which you must obtain. After understanding the cryptography rules it becomes clear that you've to run some multiplication & modulo calculations for an unknown number of cycles to obtain the final key. The number of cycles will likely be very large, so cracking this lock will take some time.

As part of the puzzle two public keys are given each having its own (unknown) number of cycles and parameters. This means that there are two paths to brute force the key, one of which being shorter. I want to be as quick as possible to keep runtime low, but it is unknown which path is faster.

I, therefore, choose to crack both keys at the same time. The

process will be complete as soon as the key is found for either of the two,

using the shortest possible number of cycles. As the calculations on both keys

are so similar the compiler vectorized it in a single

operation, basically making it as quick as cracking a single key. It

took 8419518 cycles to crack this lock, running 27.9ms. Awesome.

Results

That's it. I solved all puzzles!

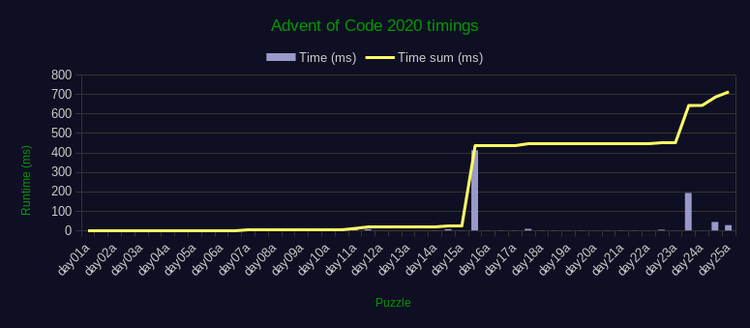

Now it was time to measure the total runtime. I've set up a simple runner for this to run and measure all my solutions in sequence.

My final solutions complete in just 699ms! That's from day 1 to day 25, 49

solutions in total, one after the other (!). Well under my 1-second

target. A fantastic achievement! Time to buy a cake.

___________

'._==_==_=_.'

.-\: /-.

| (|:. |) |

'-|:. |-'

\::. /

'::. .'

) (

_.' '._

`"""""""`

Here's a chart with all results plotted (details):

Out of interest I also ran all solutions in parallel on my

somewhat old 4-core Intel i5 CPU, which completes everything in a whopping

511ms.

Additional tricks

I did use other cool things to improve performance with which I didn't mention anywhere else. Here are some of them, most are Rust specific:

include_bytes!&include_str!: instead of reading puzzle input from a file at runtime, I embedded the file statically in the solution binary itself using these Rust macros. This removes file read operations, while still having a puzzle input file, shaving off some time.#[inline]: I suggested the compiler to inline some functions, to limit time spent by calling functions a billion times, shaving off some time.nom: an awesome Rust crate for building efficient binary parsers, used this in various places to parse tricky formats faster and more robustly than regexes or manual splitting.- Custom build flags and native optimization: for some solutions, I tweaked link-time optimization, disabled compile-time concurrency, and compiled with optimizations for my specific CPU model to shave of some time.

- Increased stack size limit: for day 15 part 2 I

increased the maximum stack size with

ulimit -s unlimitedto fit more than 8192 kilobytes on the stack frame to make the overall solution more efficient.

See the source code for more interesting stuff.

Closing words

Some have probably come up with some faster solutions than me. When I compare my solutions with others in the Advent of Code megathread on Reddit, I seem to have done very well though.

Setting this goal made this year's Advent of Code very interesting to me. It constantly required me to think about what the most efficient approach could be. This makes you creative, making your code quite elegant in many cases. If you're looking for a challenge, I recommend you to do the same. Please consider to share your cool implementations as well.

Thanks for reading folks. I hope you've gained new insight on programming challenges and have learned a thing or two. I'll see you on the 1st of December for the next Advent of Code!